How Nick Saban’s 1968 title explains the legendary coach

-

Alex Scarborough, ESPN Staff WriterJan 10, 2024, 07:00 PM ET

Close

- Covers the SEC.

- Joined ESPN in 2012.

- Graduate of Auburn University.

Editor’s note: A version of this story originally ran Nov. 14, 2018. It has been republished following news that Nick Saban will retire.

MONONGAH, W.Va. — There was no grass, no water and not much in the way of sympathy during those marathon two-a-day practices at Monongah High late in the summer of 1968. A then-16-year-old Nick Saban and his teammates were fed a strict diet of salt tablets and discipline by their coach, Earl Keener, and his assistant, Joe Ross. Cut up and bruised by that slab of red clay they called a practice field, they were tough.

There were no days without pads back then, no practices without full contact that anyone could recall. Keener was the kind of detail-obsessed drill sergeant who believed you didn’t practice until you got it right, but rather until you couldn’t get it wrong anymore.

But when Keener and Ross signaled the end of practice, Saban, a senior quarterback, would inevitably stay behind. Sometimes he’d throw extra passes; other times he’d run sprints, and without a word everyone would join in. There was something about the serious-minded Saban, whom everyone called “Brother.” He had this gravitational pull that made it obvious how much they respected him and were willing to follow his lead. It’s as if he was a blend of Keener and Ross, and most notably his father, Big Nick, who created Pop Warner football in the county. As long as there was enough light to see, he was determined to put it to use.

Keener would toss the shower room keys to team managers Walter Baransky and John Baranski and tell them to lock up when everyone was done.

“If we didn’t do a play right,” teammate Kerry Marbury said, “we’d run it until it got dark, the same play over and over until we got it right.”

“I used to get so ticked off,” Baransky said of Saban delaying dinner by an hour or more. “Damn, I’m hungry!”

But after all the time and hunger pangs have passed, Baransky and his fellow Lions understand they were witnessing the start of something extraordinary. On the 50th anniversary of Monongah winning a state championship, they remember their undefeated season and the way they dominated their schedule in Alabama-like fashion.

What’s more, they remember the way Saban was that season, and how it’s a direct reflection of the man he has become. They see him on television from time to time, their former teammate having gone on to become perhaps the greatest college football coach of all time.

“Every time I see Alabama, I’m reminded of what Nick was like,” Baranksi said. “I can feel the mentality we had 50 years ago. We expected to win.”

Monongah’s championship is still remembered in town to this day. Roger May

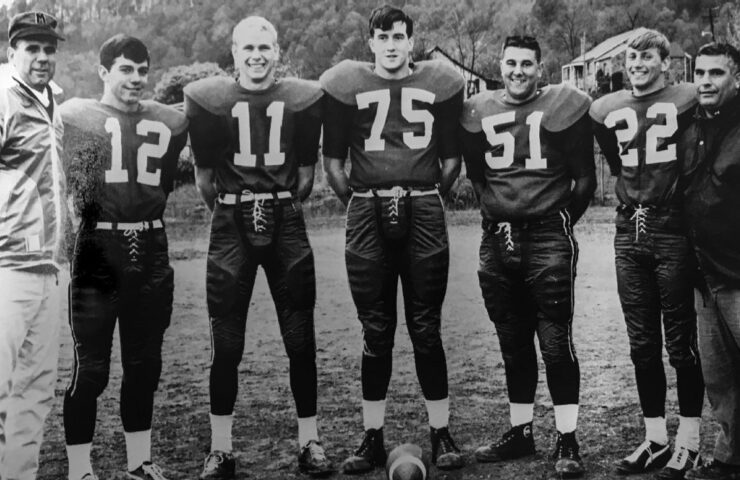

At a rural school of roughly 300 students, on a team that could dress out only 33 players because that’s all the uniforms they could afford, the Monongah Lions enjoyed more than their fair share of great players. They were so loaded, in fact, that Saban wasn’t even in the conversation for the most talented on the team.

No, the best player on the team was Tom Hulderman, a multisport star who might have played football at Alabama if not for a knee injury and was nonetheless drafted by the Chicago Cubs as a pitcher. Behind him was Marbury, who set state records in the 100-yard dash and would go on to be regarded as one of the finest running backs ever to play at WVU.

Truth be told, having Marbury and Hulderman made Saban look good. Often times, he said Keener would advise him, “I don’t care what play you call, just make sure one of those two guys gets the ball.”

It’s not that Saban wasn’t talented in his own right. He was all-state in baseball and basketball, in addition to being one heck of a quarterback. The problem was he was a few too many decimals shy of 6-foot, which took the shine off his college prospects.

When asked to provide a scouting report on himself, Saban zeroed in on, of all things, his aptitude carrying out run fakes. His skills “don’t seem to be real important now,” he said.

He can still remember the minutiae of certain calls. Like 26 Crossfire, which he said was a power run that involved the offensive line double-teaming and kicking out.

“I knew what everybody did on every play,” he added.

He could speak with authority because he was the one calling plays. Keener and Ross had input, but it was Saban who years earlier began huddling up and barking out orders of his own, which is something the vast majority of college quarterbacks are incapable of today. He may have been third best on the team in terms of pure talent, former offensive lineman Jim Pulice allowed, “but he had the brain.”

“He had a special look at football. We played great football, but Nick took it 10 levels beyond. He could walk out on the field and see a defense and catch it all.” Saban teammate Jim Pulice

“When he was on the football field … he was focused,” Pulice said. “He didn’t miss a thing. Nothing.”

Tom Ramsey can still recall Saban noticing how an opposing defense was cheating to stop the inside run. So Saban ran it up the middle once. “Pow!” Ramsey said, mimicking a stop for no gain. Then they ran it up the gut again. “Pow!” Ramsey said, again mimicking no gain. Then Saban initiated yet another inside handoff. “Pow!” Ramsey said, only grinning this time because the defense had tackled the wrong ball carrier. By the time they realized it was an end-around, Hulderman was trotting into the end zone.

“He had a special look at football,” Pulice said. “We played great football, but Nick took it 10 levels beyond. He could walk out on the field and see a defense and catch it all.”

There were other captains, but Saban was their leader. And he led much the same way he does now: with strict discipline. He was a perfectionist who demanded the same from others. “He’d get on your ass,” offensive lineman Joe Martin recalled. What’s more, his no-nonsense attitude extended beyond practice. Like once, when he noticed the towels in a crumpled-up mess, he went out of his way to remind the team managers how they used to fold them nicely after each wash rather than tossing them in the cabinet haphazardly.

“Very business-like. Very forceful,” Baranski said of Saban. “You didn’t cut up. … He would yell at this one, yell at that one what to do: ‘This guy is loafing!””

Baransky jumped in to add to the obsessive portrait: “He would even want to huddle right! Like, ‘You’re standing crooked. That’s no way to do it!'”

Amazingly, no one ever seemed to mind. They were like family, they said, with most kids having known one another since they were in preschool.

“He was just the same he is now,” Marbury said. “He is so misunderstood. People think he’s mean, he’s evil. He don’t need to kiss up to nobody. He doesn’t have to. He’s winning. Isn’t that good enough?”

Saban led his team to a 20-12 win in the state championship game despite a field that was “muddy as hell,” as the Alabama coach recalls. Courtesy of Marcus Lewis

It was obvious right away that Monongah had a point to prove. It didn’t matter that the previous year’s Class AA title game against Ceredo-Kenova wasn’t fair — C-K was so big it was forced to move up to Class AAA while Monongah was so small it had to drop to Class A — the defeat stuck with players. Even back then, Saban said, he hated losing more than he enjoyed winning.

“You felt bad,” teammate Brian Evans recalled. “But you also had it in the back of your head: We’re going to come back next year and we’re going to do this.”

In the opening game against Fairmont East, Monongah scored 14 points on its first three offensive plays, including a touchdown from Saban. The final score: 39-7. Afterward, a newspaper asked in a bold headline “Are the Lions Really that Good?” It answered in a more subtle subhead, “Many Observers Say ‘Yes.'”

In the home opener the following week, Monongah rushed for 290 yards and destroyed Morgantown University High 39-0. After that, the Lions blasted Mannington 58-7, with Saban rushing for three touchdowns. It went on that way for a while: a 53-19 thrashing of Clay-Battelle, a breezy 52-7 win at Rivesville, an absolute dismantling of Shinnston, 47-13, in which Marbury gained 165 yards on 10 carries.

A Week 7 date with unbeaten Bridgeport was supposed to be a challenge. Ron Millione, a local sportswriter at the time, noted fans’ excitement to see Monongah play the larger Class AAA school. “Instead,” as he wrote in the next day’s paper, “they saw a massacre as the No. 1 Class A team in the state completely devoured the hometown favorite, 40-0.” Afterward, another paper was caught looking ahead to the state title game a month away. “The Lions are devastatingly quick, have a tremendous passing attack and flashy speed,” it surmised.

Monongah did things no one else could. It ran laterals on kickoffs and leaned on its athleticism just as easily as it leaned into its power, using fullback Paul Deahl as a battering ram. “Mean and creative,” is how Pulice would describe the team’s identity.

“Truth be known,” he said, “we could have doubled some of those scores.”

Back home, they were celebrated. Dozens of people would come out just to watch practice. Some of the coal miners wouldn’t bother showering after their shifts, their faces covered in black dust on the sideline. “Gone to the ballgame” signs would hang in nearly every store window on Friday nights.

“Just like people relate to Alabama football, in that little town of Monongah, everybody related to the school and the games we played,” Saban said. “The last guy out of town turned the lights out when we played. That’s just the way it was. It was important.

“If we won, you got to go in Meffe’s” — a local bar — “and play the pinball machine for free. And we weren’t supposed to be in there to start with because we were underage. But if we lost they didn’t let us in the door.”

That was probably because many of the adults inside had money riding on the games. Saban said he can still picture coal miners standing behind the fence during the fourth quarter, shouting at him, “We need another score to cover. I gave 50 points for 50 bucks and it’s 49-0.”

Martin worked at the grocery store and would take bets from the bread supplier. “How many points you giving me?” he’d ask, and Martin would tell him, “How many points do you have to have?”

“I started out with two touchdowns and every week I had to give him more,” he said. “By the end of the season, I gave him 50 points for one game and I beat him.”

To end the regular season, Monongah beat Farmington, Masontown and Fairview by a combined 136-0. The Lions averaged 46.4 points per game on offense and 4.6 points per game on defense — both high-water marks in their class.

“We were beating teams 60-0 and the second-string was playing half the game,” Baransky said. “It’s just like Alabama. The same way.”

During the build-up to the state title game, a newspaper ran a headline spanning the entire page: “Keener Believes 1968 Team ‘Best Ever.'”

“Every good team has to have an outstanding leader,” Keener said. “Nick is our leader. Our boys respect him and listen to him, and when a quarterback has good judgement, this is invaluable. He is as cool and heady as a pro — for a high school boy.”

East-West Stadium, where Monongah won its crown, still stands today. Alex Scarborough/ESPN

It was a cold and damp afternoon at East-West Stadium when Monongah prepared to play Paden City for the Class A State Championship.

Saban’s squad was favored, but Mother Nature did her best to level the playing field.

The grass field was already in rough shape given that seven area high schools used it during the season, as well as Fairmont State University. Then rain battered the area for what felt like an entire week, making an already unreliable surface even more treacherous.

“It was muddy as hell,” Saban said.

No one knew it at the time, but Saban was dealing with a chipped bone in an ankle and Hulderman an injured knee. No one was able to get a decent footing on the field, though.

Monongah scored first on a 29-yard run by Marbury. Then, on fourth-and-goal, Marbury found the end zone again. But the Lions couldn’t pull away. The conditions wouldn’t allow for it.

Saban attempted only three passes and completed none.

Paden City made a push, scoring 12 unanswered points to cut the lead to two. But then, with 1:36 remaining, Marbury threw a block that sprung Deahl for a 62-yard game-clinching touchdown. The final score: 21-12.

Confetti was thrown in the stands as fans crowded the field, but none of the players felt much like celebrating. They hardly smiled. They were too exhausted, covered in slop up to their ears, wet and generally miserable.

“We worked to get there and all of the sudden — bam!” Evans said. “Guys were worn out from playing in that mud.”

Besides, he added, “We weren’t used to playing four quarters.”

After they showered and changed, everyone went to Say-boys for steak and a baked potato. Saban sat at the middle of the table, his eyes trained on his plate rather than the trophy directly in front of him. He’d get to play pinball at Meffe’s later, but according to him, “That was it,” in terms of postgame fun.

It’s not that he didn’t enjoy the victory. Everyone did. But for Saban, even back then, it was all about moving on to what’s next. And at the time, his future couldn’t have been any more uncertain.

Fifty years later, his attitude hasn’t changed. “He doesn’t live in the past,” Marbury said. “He’s learned from it.” He wasn’t able to attend a celebration of the championship team last month — it was a bye week and he was busy recruiting — but in a recorded message he referred to many of his teammates as “lifelong friends” and called the memory of the season one “I’ll never forget.”

“I always say that the first championship that we won in 1968 means as much as any national championship or any other championship that we ever won,” Saban said. “And that’s because of the players on the team and the guys that are there today that that all was possible.”

In high school, Saban was a letter-winner in basketball, baseball and football, as well as class vice president and a member of the dance club. Courtesy of Marcus Lewis

Somewhere in a stack of papers lost to history is a letter written by the late West Virginia Sen. Robert Byrd. In it is the path Saban might have taken: a nomination to attend the Naval Academy.

Even as late as the publication of the 1969 Monongah yearbook, Saban was listed among the Service Academy appointments. And it’s easy to see why. The blurb beside his picture reads like the resume of a future world leader: letterman in baseball, basketball and football; Class Vice President; part of the Latin Club, Guidance Club and National Honor Society; Yearbook Editor-in-Chief; County and State Chairman of Clean-up Committee; Chairman of Homecoming Week-end; Elks Leadership Contestant; Class Tournament Coach; and, of all things, a member of the Dance Club.

A future in college football was more a hope than anything tangible.

“Recruiting was different back then,” he said. “… It wasn’t a big thing. Nobody knew anything about it.”

Ohio University and Miami (Ohio) sniffed around. He attended Bennie Friedman’s Quarterback School in New York but drew only “feelers” from Penn State and Michigan. A newspaper headline said it all: “Monongah’s Saban, Fading Star Seeking a Galaxy.”

“Some big school is really missing out if they don’t give Nick a chance,” Keener said. “The kid has more heart than any I’ve ever seen in 30 years of coaching. All he knows how to do is beat you.”

It’s true. During Saban’s four years of high school, he forged a record of 50-1-1. But, again, all recruiters saw was his 5-foot-10 frame. That WVU wasn’t interested “broke his heart,” according to teammate Ron Rhodes.

It wasn’t until Kent State and coach Don James came calling that everything clicked. Theirs might not have been the glamorous offer, but it turned out to be the right one. Saban would play quarterback on the freshman team until a coach asked if he’d like to try his hand at defensive back during spring practice.

“I could probably do all the things the other quarterbacks could do, but I couldn’t see,” Saban said. “And I kind of knew. I could see that. I knew I was good enough to play somewhere.”

When he finished his senior season at Kent State, he believed he was finished with football altogether. He had plans to attend Northwood Institute and learn how to run a car dealership when James called him into his office and asked him to stay on as a graduate assistant. “I’m sick of going to school,” he told James. “I don’t really have any aspirations of being a coach.” But James was shrewd and used Saban’s wife, Terry, as leverage, pointing out how she had another year of school to complete.

Saban relented, got his master’s degree and accidentally caught the coaching bug.

“Hell,” he realized, “this is just like playing. I love it. It’s the competition of the game, you’re working with players every day, you’re breaking down film, all this stuff.”

“He was just the same he is now. He is so misunderstood. People think he’s mean, he’s evil. He don’t need to kiss up to nobody. He doesn’t have to. He’s winning. Isn’t that good enough?” Saban teammate Kerry Marbury

That he stumbled into learning at the feet of a future Hall of Fame coach was a stroke of luck.

“You couldn’t have ended up in a better place than he did,” teammate Chris Yanero said. “All the pieces fell in the right place for him.”

Seventeen years and a handful of stops later, Saban became the head coach at Toledo. Then, in 2004, he won the second championship of his life at LSU.

Now he’s firmly entrenched at Alabama, having won a ring for every finger on his right hand. He’s working on starting a collection on his left this season, as the Crimson Tide are once again ranked No. 1.

According to nine of his fellow Monongah Lions interviewed for this story, absolutely nothing has changed about him since that summer in ’68. He’s still a “hard-ass.” He’s still “no-nonsense.” He still has a “head for the game.” The legacy he left behind their tiny hollow of West Virginia is the same as it will be when he leaves Alabama: “It was getting your butt in gear,” Yanero said. “You practiced hard and you played hard.”

Saban may not have known it back then, rolling around in the dust and mud during two-a-days, but his destiny was “coming out one way or another,” according to Pulice and the rest of his teammates. He may not have seen himself as a coach in the making, but they already knew the teenager to be their coach on the field.

Everyone was tired by the time Keener would signal the end of those grueling practices and yet they’d stay behind because their quarterback would.

It didn’t need to be said why. Dinner could wait. Brother was going somewhere and they were compelled to follow.